A site to Explore

Publications

General

Information about specific tribes follows this section

Image: Legends of the Kaw

Bernhardt, C. (1910). Indian raids in Lincoln County, Kansas, 1864 and 1869; Story of those killed, with a history of the monument erected to their memory in Lincoln court house square, May 30, 1909. Lincoln, KS: Author. Bernhardt collected numerous accounts regarding Lincoln County settler attacks. Various incident versions are provided along with maps, letters, property listings, and other records. Wrote Thomas Moffitt, written July 30, 1864, six days before Indians killed him near Beaver Creek on the north bank of the Saline River: “We were doing very well and would do as well now if it were not for the Indians. We would make five or six dollars a day hunting buffalo, but we have been obliged to give it up for the present. The Indians are so hostile to the hunters and settlers that we dare not go from the house. When we have to go we go armed. Even when we go to the stable to take care of the horses we carry our revolvers along; rather hard lines these from what we have been used to. The government has sent out several companies of soldiers, but they can’t fight the Indians as well as settlers themselves. Some of the folks that have families are leaving Salina for a more safe place. Some expect there will be a regular Indian war, but I don’t think there will be any trouble in the settlement from the Indians.”

This brief history of tribes in Kansas, Nebraska. and Iowa describes individual tribes.

Cody, William F. (1917). Life and adventures of "Buffalo Bill," Colonel William F. Cody. Chicago, IL: Stanton and Van Vliet Co. In Cody's biography, he tells of his many Indian encounters, including his introduction to the Kickapoo by his childhood home in Leavenworth. "[Father] He visited the Kickapoo agency in Leavenworth County and soon after established a trading post at Salt Creek Valley, within four miles of the agency. Having thus entered into business, he settled his family on a farm belonging to Elijah, three miles from Weston, intending that we should remain here until the territory was opened up for settlement. At this time Kansas was occupied by numerous tribes of Indians who were settled on reservations, and through the territory ran the great highway to California and Salt Lake City. In addition to the thousands of gold-seekers who were passing through Kansas by way of Ft. Leavenworth, there were as many more Mormons on their hegira from Illinois to found a new temple in which to propagate their doctrines. This extensive travel made the business of trade on the route a most profitable one. . . .During the summer of this year we lived in our little log house, and father continued to trade with the Indians, who became very friendly; hardly a day passed without a social visit from them. I spent a great deal of time with the Indian boys, who taught me how to shoot with the bow and arrow, at which I became quite expert. I also took part in all their sports, and learned to talk the Kickapoo language to some extent. Father desired to express his friendship for these Indians, and accordingly arranged a grand barbecue for them. He invited them all to be present on a certain day, which they were; he then presented them with two fat beeves, to be killed and cooked in the various Indian styles. Mother made several large boilers full of coffee, which she gave to them, together with sugar and bread. There were about two hundred Indians in attendance at the feast, and they all enjoyed and appreciated it. In the evening they had one of their grand fantastic war dances, which greatly amused me, it being the first sight of the kind I had ever witnessed. My Uncle Elijah and quite a large number of gentlemen and ladies came over from Weston to attend the entertainment. The Indians returned to their homes well satisfied. My uncle at that time owned a trading post at Silver Lake, in the Pottawattamie country, on the Kansas river, and he arranged an excursion to that place. Among the party were several ladies from Weston, and father, mother and myself. Mr. McMeekan, my uncle's superintendent, who had come to Weston for supplies, conducted the party to the post. The trip across the prairies was a delightful one and we remained at the post several days. Father and one or two of the men went on to Fort Riley to view the country, and upon their return my uncle entertained the Pottawattamie Indians with a barbecue similar to the one given by father to the Kickapoos."

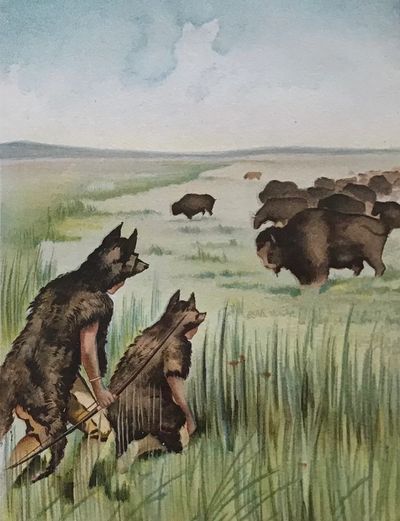

DeVoe, Carrie. (1904). Legends of the Kaw: The folk-lore of the Indians of the Kansas River Valley. Kansas City, MO: Franklin Hudson Publishing. Besides descriptions of tribes in Kansas and charming illustrations, Devoe presents oral history accounts and beliefs. "There was an idea, current among the Indians who roamed over the central portion of the United States, that at one time in the long past, the rivers of the Mississippi basin filled the entire valley, and only great elevations were visible. Geology substantiates this teaching. The theory of a dual soul approached very close to the teachings of modern psychologists. While one soul was supposed to remain in the body, its companion was free to depart on excursions during sleep. After the death of the material man, it went to the Indian elysium and might, if desirous, return, in time, to earth, to be born again." Thunder and lightning, for example, were seen by some as a struggle between the God of Waters and the Thunderbird and by other as the voice of the Great Spirit reminding of corn-planting season. The Sioux storm giant's horns looked like lightning and used the four winds as drumsticks to produce thunder. DeVoe tells of entities such as the

Wild Parsnip who did bad deeds and was forced by magic to stay in one place where he killed people when they ate him and the Spirit of Fire who rode in a cloud of smoke and shot flaming arrows that spread prairie fires.

Drimmer, Frederick, ed. (1961). Captured by the Indians: 15 firsthand accounts, 1750-1870. New York: Dover. Intermingled with the grisly tortures, adoptions, and miraculous escapes are snapshots of capricious personalities, various customs, amusements, battle philosophy, and tribal reactions to the westward push of settlers. Several tribes who would come to Kansas are represented.

Gates, Paul. (2021). Indian allotments preceding the Dawes Act. The Frontier challenge: Responses to the TransMississippi West. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. By 1854, 8,002 members of different tribes had been placed in Kansas, according to reports. “There, on clearly defined reservations they dwelt in misery, partly sustained by inadequate government aid and denied the freedom from white intrusions that their treaties had guaranteed them.” They had been promised their reservations 'in full and complete possession. . . as their land and home forever.' However, passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act brought land-hungry individuals who ignored Indian ownership and made Kansas an undesirable environment for tribes. Between 1854 to 1861, tribes in Kansas would sign 14 new treaties surrendering their reserves."

Haskell Institute. (1914). Indian legends. Lawrence, KS: Haskell Printing. Students tell of stories they heard from their parents and elders with titles such The Man Who Became a Fish or How Loneliness Created Prairie Dogs.

Herring, Joseph B. (1990). The enduring Indians of Kansas: A century and a half of acculturation. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. Herring delves into the complexities of emigrant tribes’ forced relocation to Kansas and addresses the impact of acculturation and tribal refusal to assimilate. Chapters include focus on the Kickapoo, Chippewa and Munsee, Iowa and Missouri Sac, Mokohoko’s Sac, and Prairie Potawatomie. Herring wrote: "During the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s more than ten thousand displaced Indians settled ‘permanently’ along the wooded streams and rivers of eastern Kansas, at the edge of the western prairie. By the early 1870s, however, there remained only several hundred Kickapoos, Potawatomis, Chippewas, Munsees, Iowas, Sacs, and a few others. These Indians were still in Kansas because they had managed to walk the fine line between their traditional ways and those of the whites. Although the Kickapoos, Potawatomis, and others had accultured, they had not assimilated into the dominant American culture.”

Hoard, Robert, & Banks, William, eds. (2006). Kansas archaeology. Lawrence, KS: University Press. The majority of this books reports on inhabitants living in Kansas before European contact and found artifact significance. Chapters on the Wichita, Kansa, and Pawnee provide extensive documentation on their village sites in Kansas. An excerpt from the book's introduction reads: From Kanorado to Pawnee villages, Kansas is a land rich in archaeological sites—nearly 12,000 known—that testify to its prehistoric heritage. This volume presents the first comprehensive overview of Kansas archaeology in nearly fifty years, containing the most current descriptions and interpretations of the state's archaeological record. Building on Waldo Wedel's classic Introduction to Kansas Archaeology, it synthesizes more than four decades of research and discusses all major prehistoric time periods in one readily accessible resource. . . .The findings presented here shed new light on issues such as how people adapted to environmental shifts and the impact of technological innovation on social behavior. Included also are chapters on specialized topics such as plant use in prehistory, sources of stone for tool manufacture, and the effects of landscape evolution on sites. Chapters on Kansas culture history also reach into the surrounding region and offer directions for future inquiry. More than eighty illustrations depict a wide range of artifacts and material remains."

Irving, John T., Jr. (1835). Indian sketches taken during an expedition to the Pawnee and other tribes of the American Indians, Vol 1. London: John Murray. Irving shares stories and impressions of his travels encountering the Otoe, Sac, Shawnee, Kickapoo, Kansa, Pawnee, and others. "So—these are the Indians! This is a specimen of the princely race which once peopled the wilds of America, from the silent wilderness which still borders the Pacific, to the now humming shores of the Atlantic! We were disappointed, and did not reflect that we were looking only upon the dregs of that people; that these were but members of those tribes who had long lived in constant intercourse with the whites, imbibing all their vices, without gaining a single redeeming virtue; and that the wild savage could no more be compared with his civilised brother, than the wild, untamed steed of his own prairie could be brought in comparison with the drooping, broken-spirited drudge horse, who toils away a life of bondage beneath the scourge of a master." Irving even devotes a chapter to Indian dogs. "There are no greater thieves in existence than the Indian dogs; not even excepting the old squaws, who have made it their amusement for half a century. With the last it is a matter of habit and practice; but with the former it is instinct. It is necessary for their existence that they should be at the same time accomplished thieves and practised hypocrites. They are never fed by their masters, who are always particularly careful to keep every eatable from their reach, their own appetites being generally sufficient to dispose of every thing of that nature. As far as I was able to judge, the only act of pastoral kindness which they ever exerted over their canine flock consisted in flogging them whenever a chance offered. There is scarcely a lodge which does not patronise at least a dozen of these hangers-on, who, with all their thievishness, are the most pious-looking dogs in existence." . Irving describes his experiences meeting several tribes while on his way to meet the Pawnee in Kansas. About the Pawnee, he wrote: "Upon our near approach, we could perceive that the hills surrounding it were black with masses of mounted warriors. Though they swarmed upon their tops, to the number of several thousands, yet they stood motionless and in silence, watching the approach of the mission. At length a single horseman detached himself from the mass, and came galloping down the hill and over the prairie to meet us. As he approached, there was a wild, free air about him, and he governed his gigantic black horse with the greatest ease. I could not but think that if the rest of these warriors were of the same mould, any resistance of our band, however desperate, would avail but little against an attack of these proud rulers of the prairie. Upon reaching the party, he sprang from his horse, and shook hands with Mr. E——. He then gave directions, through the interpreter, that the band should be drawn up in as small a compass as possible, to avoid all contact with his warriors. After spending some time in completing his arrangements, he galloped back, and gave the signal to the rest. In an instant the hills were deserted, and the whole mass of warriors were rushing towards us, across the broad bosom of the prairie. It was a moment of intense and fearful expectation. On they came; each mad horse with erect mane and blazing eye, urged forward by the bloody spur of an Indian master. They had reached within two hundred yards of the party, but still the speed of their horses was unchecked, and the powerful tramp of their hoofs rang like thunder upon the sod of the prairie. At a signal, however, from the chief, the band separated to the right and left, and commenced circling round us, in one dark, dense flood. Their whoops and yells, and the furious and menacing manner in which they brandished their bows and tomahawks, would have led a person unacquainted with their habits to have looked upon this reception as any thing but friendly. There is something in the fierce, shrill scream of a band of Indian warriors, which rings through the brain, and sends the blood curdling back to the heart. Their ornaments, though wild, were many of them beautiful. The closely shaved heads of some were adorned with the plumage of different birds. Others wore an ornament of deer’s hair, bound up in a form resembling the crest of an ancient helmet; and a plume of the bald eagle floated from the long scalp-locks of the principal warriors. Some few wore necklaces of the claws of the grisly bear hanging down upon their breasts. The bodies of some were wrapped in buffalo robes, or the skin of the white wolf; but the most of them wore no covering, save a thick coat of paint. This they had profusely smeared over their bodies and arms, and many had even bestowed it upon the heads and limbs of their horses. After dashing round us for some time, the chief waved his hand, and the turmoil ceased. The warriors sprang from their horses, and, seating themselves round in a large circle, waited for the arrival of the chief of the Grand Pawnees."

Lowie, Robert. (1954). Indians of the Plains. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. Individual traits and shared commonalities including food, dwellings, dress, ceremonies, social organization, recreation, and other topics are covered in this detailed narrative. The European contact impact also is discussed, for example: "An important personality problem, for the males, was finding a suitable substitute for old goals. With the buffaloes gone and war a thing of the past, they found it very hard to discover any objectives that made life worth living (p. 196).

Miner, H. Craig, & Unrau, William E. (1977). The end of Indian Kansas: A study of cultural revolution, 1854-1871. Lawrence, KS: Regents Press of Kansas. When Kansas became a U.S. territory in 1854 literally all of its land area was guaranteed by treaty to tribes with more than 10,000 members. This book details the forced removal between 1854 to 1871 used by land speculators, railroad companies, and others to seize the lands of tribes, policy incongruities, and tribal contributions to land loss. As one review stated: "There are no heroes in this narrative of fraud, corruption, and violence by the military, the executives of state and federal governments, legislators, businessmen, lawyers, settlers, and Indians."

Powers, Ramon, & Leiker, James. (1998, Autumn). Cholera among the Plains Indians: Perceptions, causes, consequences. Western Historical Quarterly, 29 (3), 317-340. Powers and Leiker tell of cholera’s impact on various Indian tribes while exploring their central question: Why was there a marked difference in death rates between Indians and non-Indians? Included in their discussion are death rates from the 1849-1852 epidemics in Kansas. Jotham Meeker, missionary, for example, wrote 50 members of Iowa and Sac Fox died of cholera, more than a hundred Kansa, and six at the Delaware Baptist Mission and six in Wyandotte during that epidemic. Dr. W. H. Tinglery, an army medical officer traveling west of Fort Leavenworth in 1851 found "fearful mortality" at a Potawatomi settlement with 40 Delaware, Shawnee, Munsee, and Stockbridge dead from the disease. The 18 Potawatomi at St. Mary Mission who died of cholera, according to local legends, were buried in a common grave near present Uniontown cemetery and also near the Potawatomi Baptist mission. The authors cite the 1849 California gold rush as attracting those who carried the disease that infected Indians on Arkansas River, especially the Kiowa who said half of their tribe members died. Cholera seemed to fade away after 1852 but returned in the mid-1860s when Kansas soldiers moved 1,200 Wichita and spread the disease even before the move took place. “On their way through southern Kansas in 1869, a party of travelers viewed a sad reminder of the recent conquest: the unburied remains of scores of Wichita Indians, struck down two years earlier by a cholera epidemic. An observer later claimed that at least one hundred graves were scattered over the side of present-day Wichita, while at nearby Skeleton Creek so many Indians had perished that they could not be buried, hence, the creek’s name (p. 317)."

Stratton, Joanna. Pioneer woman: Voices from the Kansas frontier. New York City, NY: Simon Schuster. Stratton includes the chapter "The Clashing of Cultures: Indians" that provides glimpses into settlers' encounters with tribes in Kansas. Discussing fear, Mary Gettys Lockard said: "We had been told that there were no hostile Indians in Kansas, but just the same we could remember the horrible tales of Indian depredations further west the continued to sift in to trouble us. We had a book that gave some of Jim Bridger's philosophy, and in one place he was quoted as saying 'wha're you don't see no Injuns, tha're they are the thickest' that gave me the fixed idea that Indians rose up from the ground at times and killed everybody in sight. We children talked about Indians so much it got on my mothers' nerves not a little, and she had a hard work trying to stop our chatter about them (p. 112)."

Unrau, William. (2007). The rise and fall of Indian Country, 1825-1855. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. Book description: “The Indian Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834 represented what many considered the ongoing benevolence of the United States toward Native Americans, establishing a congressionally designated refuge for displaced Indians to protect them from exploitation by white men. Others came to see it as a legally sanctioned way to swindle them out of their land. This first book-length study of 'Indian country' focuses on Section 1 of the 1834 Act—which established its boundaries—to show that this legislation was ineffectual from the beginning. William Unrau challenges conventional views that the act was a continuation of the government's benevolence toward Indians, revealing it instead as little more than a deceptive stopgap that facilitated white settlement and development of the trans-Missouri West. Encompassing more than half of the Louisiana Purchase and stretching from the Red River to the headwaters of the Missouri, Indian country was designated as a place for Native survival and improvement. Unrau shows that, although many consider that the territory merely fell victim to Manifest Destiny, the concept of Indian country was flawed from the start by such factors as distorted perceptions of the region's economic potential, tribal land compressions, government complicity in overland travel and commerce, and blatant disregard for federal regulations. Chronicling the encroachments of land-hungry whites, which met with little resistance from negligent if not complicit lawmakers and bureaucrats, he tells how the protection of Indian country lasted only until the needs of westward expansion outweighed those associated with the presumed solution to the 'Indian problem' and how subsequent legislation negated the supposed permanence of Indian lands. When thousands of settlers began entering Kansas Territory in 1854, the government appeared powerless to protect Indians—even though it had been responsible for carving Kansas out of Indian country in the first place.”

Vučković, Myriam. (2008). Voices from Haskell: Indian students between two worlds, 1884-1928. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. In 1884, 22 Ponca and Ottawa children were enrolled to be taught Anglo-Protestant cultural values at the boarding school. Since that time, tens of thousands for students from numerous tribal heritages have attended school, which has changed with the times.

Also view:

Delaware

Farley, Alan W. (1955). The Delaware Indians in Kansas: 1829-1867. Kansas City, MO: Author.

Originally a paper read in 1955 to the Kansas City Posse of the Westerners, this 16-page booklet encompasses far more than Delaware residence in Kansas and includes missions, trading posts, ferries, skirmishes with Pawnees, treaties, reservations, and final removal of Delaware from Kansas. "Many of the Delaware settled and built rude cabins along the military trail leading from the crossing to Fort Leavenworth. Some of the more prosperous members of the nation built more pretentious homes and farmed, eventually more than 1,500 acres on the reserve coming under cultivation. But a large proportion of the tribe loved to roam the plains in pursuit of buffalo." (p.4).

Obermeyer, Brice, & Bowes, John. (2016). The lands of my nation: Delaware Indians in Kansas, 1829-1869. Great Plains Quarterly, 36(1), 1-30. Obermeyer and Bowes thoroughly detail the complexities of obtaining reservation land in Kansas, keeping it, and being relocated when the treaty dissolved in 1866, and obtaining their own land. To come to Kansas, the Osage and Kansas had to give up their land in the 1829 treaty signed by 11 Delaware, who, in turn, gave up their land in southwest Missouri on the James Fork of the White River for their Kansas reservation at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers. The Delaware also received a 10-mile wide land strip that led into land of the Pawnee to Pawnee ire. The majority of Delaware came to what would be Kansas by 1831, building homes in the eastern third of the reservation and along Stranger Creek and missions. They did business in Fort Leavenworth and traveled working in the fur trade. In 1846, an estimated 1,132 Delaware lived on the reservation. An 1863 report noted the one brick, 51 frame, and 250 log houses on the Delaware-owned land with many farming more than 50 acres. The tribe let the Munsee and Stockbridge live on some land, sold land to the Wyandotte removed from Ohio, ceded land to the U.S. government for settlers, set aside land for a group intertwined with the Delaware known as the Christian Indians that numbered about 200 individuals. After years of harassment by trespassers, squatters, and thieves, the Delaware agreed to sell the remainder of their reservation land. They didn’t have a place to go and the Indian Territory didn’t have any open land. But they finally were able to buy land from the Cherokee in 1867, a decision that would leave them a landless tribe without federal recognition.

Kansa

Dixon, Benjamin. (2007). Furthering their own demise: How Kansa Indian death customs accelerated their depopulation. Ethnohistory, 54(3). Advancing his thesis that the Kansa’s death customs increased their depopulation, Dixon also presents a view of the Kansa during the 1800s.

Johnson, Alfred. (1991). Kansa origins: An alternative. Plains Anthropologist, 36(133), 57-65. Johnson examined data and suggests that Kansa sites in northeastern Kansas might be Oneota sites instead and that the Kansa ancestral territory was south of the Kansas River.

Parks, Ronald. (2015). Civilization of the American Indian: The darkest period: The Kanza Indians and their last homeland, 1846-1873. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. According to its description, “Parks does not reduce the Kanzas’ story to one of hapless Indian victims traduced by the American government. For, while encroachment, disease, and environmental deterioration exerted enormous pressure on tribal cohesion, the Kanzas persisted in their struggle to exercise political autonomy while maintaining traditional social customs up to the time of removal in 1873 and beyond.”

Remsburg, George. (1911). An old Kansas Indian Town on the Missouri. Plymouth, Iowa: Chandler.

Remsburg presents his argument for the Doniphan location as the site of an early Kansa village in this 24-page booklet replete with artifact-finding anecdotes.

Waggoner, Tricia J. (2018) Excavations at Fool Chief’s Village (14SH305). Topeka, KS: Kansas Historical Society. The “Historical Background” chapter furnishes a narrative bolstered by archaeological find. For example, the Donipahn area was the first Kansa village documented site when visited by Étienne Veniard de Bourgmont and said by the group’s medical officer to have 150 houses and using horses but retaining dogs as pack animals. A 1718 map also notes the site that the 1804 Lewis and Clark expedition found in ruins at the mouth of Independence Creek. The Kansa continued moving southwest and traded furs for European manufactured goods.

Wedel, Waldo. (1946). The Kansa Indians. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science, 49 (1), pp. 1-35. Wedel details numerous aspects of the Kansa setting their story with a reference to Thomas Say, a scientist with Major Long’s 1819 expedition, who visited a Kansas village and reported. "Linton cites Dorsey as stating the Kansa were at one time united with the Osage with whom they shared language similarities, Omaha, Ponca, and Quapaw. They all resided by the Ohio River before separating. Linton summed up the Kansa as continually struggling to survive and "were never a large or powerful tribe, nor were they an especially influential factor in frontier affairs. For a brief time in the late 18th century they stood athwart the Missouri River, blocking passage of the traders bound for the upstream tribes (p. 2).” He then wrote they had a reputation as thieves and beggars but never fought against the U.S. government. Historically, the Kansa lived in northeastern Kansas and presents a table with village, lodges, warriors, and total population estimates from 1,723 to 1,900 and a drop to 217 in 1900 from 1,500 in 1800. Initially, they had villages on the Missouri River, then the Kansas River, and finally on the Neosho River. Wedel describes the lodgings and other details about these villages.

Omaha

Street, William D. (2015). Twenty-five years among the Indians and buffalo: A frontier memoir. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. In the chapter "An Omaha Indian Buffalo Hunt in Northwestern Kansas: October 1873. Street wrote about observing Omaha hunt in what is now Cook Township in Decatur County that began when Street’s group shot a buffalo. "From a peaceful, quiet landscape with only a small herd of buffalo running away from a lone hunter, a team and wagon with two men moving toward him as if by magic, possibly at a given signal from the chief, came Indians as by the scores, mounted on their fleet hunting ponies. They appeared in groups of from four to five to more than twice that many every direction around the fleeing herd. It was unconveyable to we who had been on the constant lookout for game without a thought of Indians that the prairie-expanse before us should contain so many concealed living beings. Whether they had observed us or not— in all reason they had—they were apparently not quite ready for the attack on the herd, but the running buffalo were met in the west by a strong force of hunters who turned them to the north, there to meet another line of Indian hunter to turn them to the east where they were met by other Indians to circle them off southward and then others to circle them to the west where the scattering remnant of the herd were apparently wiped out. After the first turn, the dead buffalo were strung out around the circle, and at each turn the number of hunters was increased by those of that side, or line, joining in the chase. They would break into the outer flank of the herd, and close in as short range, shouting and shooting, all the time. Some were using carbines, some riffles some pistols, and other bows and arrows.”

Osage

Burns, Louis F. (2004). A history of the Osage people. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. Writing from the Osage perspective, Burns uses oral traditions and research to tell the Osage history.

Edwards, Tai. (2018). Osage women and empire: Gender and power. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. Book description: “. . . Osage cosmology defined men and women as necessary pairs; in their society, hunting and war, like everything else, involved both men and women. Only by studying the gender roles of both can we hope to understand the rise and fall of the Osage empire. . . .Once confronted with US settler colonialism, Osage men and women increasingly focused on hunting and trade to protect their culture, and their traditional social structures—including their system of gender complementarity—endured.”

Kaye, Francis. (2000, Spring). Little squatter on the Osage diminished reserve regarding Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Kansas Indians. Great Plains Quarterly, 20, 123-140. Kaye compares Laura Ingalls Wilder’s 1935 account of the Osage in her Little House on the Prairie novel with the Osage point of view. Wilder’s narrative chronicles from 1869 to 1871 when the Ingalls lived 10 miles south of Independence, Kansas, when Wilder was three years old. By 1870, the Osage were frustrated by the 1862 Homestead Act; the leave taking of more than 10,000 members of various tribes from Kansas lands they had been promised in perpetuity; the decimation of crops from grasshoppers and drought; the guarding by the Arapahos and Cheyenne of diminished buffalo herds from Osage and others; harassment from settlers; and an estimated 15,000 squatters on Osage land waiting to claim the land when treaties fell through. Kayes relates how Wilder more often describes the Osage negatively, e.g., “naked, wild men,” who are “dirty and scowling” with eyes “black and still and glittering, like snake’s eyes.” Wilder writes of the Osage demanding food that from the Osage point could have been justified as a way to obtain rent for their land. One of the few positives noted about the Osage is the helpful Soldat du Chene, an Osage, scholars have not been able to identify and suspect was fictional. The Osage and Ingalls stories end the same: they were forced to leave the land in Kansas. The Osage eventually sell their land and buy land in Oklahoma. Charles Ingalls’ gamble that rules would change allowing him to obtain free land was unrealistic from the start. By 1869, it was clear that Osage land or Cherokee Strip was not going to be available by homestead or preemption. Besides blaming Wilder for a biased account of the Osage, Kaye blames Wilder’s audience. “Readers’ easy acceptance of the Noble Savage-Indian uprising subplot of Little House on the Prairie, along with Wilders’ self-serving interpretation of her family’s right to build their little house in the first place and the ‘innocent victim’ explanation for their leaving Kansas, are not as astounding as they might be if readers and critics were not themselves mostly of European descent, hoping deeply to discover that the dispossession of Indian America was a wonderful epic.” (188) If readers had the opportunity to learn about the Osage complex land difficulties regarding their Kansas land as so laid out by Kaye, they might view the Ingalls family view of the Osage differently as might the Ingall family, too."

Reeves, Carroll Don. (1961). History of the Osage Indians before their allotment in 1907. North Texas State College. Chapter three describes problems the Osage had in Kansas. Reeves concludes that chapter with: "The Osages' plight in Kansas may be summarized by one word, poverty. And this poverty had resulted from three major causes: the hostility of the Plains tribes, the encroachments of white settlers, and the inefficient and poorly administered policy of the Federal Government. By 1869, these problems had forced the tribe to move to the Indian Territory. Ironically, they had to pay the Cherokees seventy cents an acre for lands which that tribe had previously taken from the Osages."

Tinker, George E. (n.d.). The Osage: A historical sketch. This edited publication contains articles, letters, and listings about treaties, Confederate massacre, oil rights, and other topics. George Edward Tinker (1868-1947) was born at the Osage Mission in Kansas. He served on the Osage Tribal Council and had several publishing ventures.

Pawnee

Image: Pawnee sacred bundle. Source: Linton article.

Linton, Ralph. (1923). Annual ceremony of the Pawnee medicine men. Chicago, IL: Field Museum of Natural History. Linton based this description on the field notes of George A. Dorsey and wrote: “In every Indian tribe there were a number of persons, called medicine men by the whites, who were regarded as the possessors of supernatural powers which enabled them to recognize and cure disease. They were believed to have received their powers from some supernatural being either as a direct give or as the result of instruction by some person who had received such powers. Although they frequently employed sleight of hand and other trickery to impress the uninitiated, many of them believed that they really possessed the powers attributed to them and performed their ceremonies in good faith. Ins some cases they combined the functions of a shaman or priests with that of a healer, and thus exercised great influence over the people. In most of the populous tribes they were organized into guilds or societies. Among the Pawnee, the medicine men ranked socially next to the chiefs and priests. They usually wore a distinctive costume consisting of a buffalo robe with the hair out, a bear’s-claw necklace, and a cap of beaver skin. They also wore charms or amulets consisting of the tail and claws of the wild cat, badger, or bear, bear’s ears, miniature pipes, and downy feathers attached to a bandoleer or beads and seeds” (pp. 55-56). Medicine men kept their roots, paints, clay, animal bones, buffalo maw stone, and other objects in a bag that were handed down to future generations. Herbs brewed into a tea were used for known ailments. Unknown diseases were viewed as witchcraft cured only by a counter spell or sucking out the curse and throwing it in a fire while shaking rattles and singing. They also used pikawiu, a form of hypnotism, to pull out evil influences."

Linton, Ralph. (1922). The Thunder Ceremony of the Pawnee. Chicago, IL: Field Museum of Natural History. Before explaining the Thunder Ceremony, Linton explains Pawnee diety hiearchy starting with Tirawa the supreme god followed by his wife who represented heaven, and then, Evening Star who had a garden full of corn and many buffalo and was assisted by Wind, Cloud, Lightening, and Thunder. These and minor sky gods linked with stars while additional earth-derived gods were associated with animals. Priests aided by medicine men performed ceremonies that usually involved each village’s sacred object bundle (see image to right) typically consisting of tobacco, pipe, paints, bird skins, and corn. Ceremonies with rituals dramatizing the story of supernatual beings and ended with an offering or sacrifice, which could be human. The foundation of all ceremonies and the spring ceremony of welcome was the Thunder Ceremony done to ensure crops and buffalo hunts. The ceremony took place with first thunder heard in spring. Participants gathered to shake rattles and repeat song verses many times that concluded with priests making grunting sounds to symbolize thunder. Nine sacrifices of dried meat placed in a fire then were made to various dieties. The tenth sacrifice consisting of tobacco, beads, and a scalp. Objects from the village’s sacred bundle were waved through a fire’s smoke, then participants passed through smoke. Then participants ate corn and other food, told stories and left the ceremony site in unison. Linton based this description on the field notes of George A. Dorsey.

Potawatomi

Image: St. Marys misson in 1867. Source: Alexander Gardner.

Burke, James M., ed. (1953, August). Early years at St. Mary’s Pottawatomie Mission: From the diary of Father Maurice Gailland, S. J. Kansas Historical Quarterly, 20, 501-529. His accounts note baptisms, Mass, weather, building progress, visits, deaths (several from cholera), and incidental facts such as the Kansa spending time outside the mission and the “innumerable” travelers bound for California “lavishly squandering their counterfeit money and stealing horses” (p. 520) Gailland also wrote about a conflict between the Potawatomi and Pawnee: “We live in anxiety about the success of the new mission; for our Indian people continue in the settlements on either side of the river. The anxiety is increased by the rumours of a war that is imminent between the Potawatomies and the Pawnees. For not so long ago, the Kansas Indians, while out hunting with the Potawatomies, met the Pawnees and fired upon them, and the Potatwatomies seeing themselves involved in the common danger rushed into battle for their own safety and killed many Pawnee warriors and ponies. Burning with revenge for this, the Pawnees have foresworn their old friendship for the Potawatomies. They are raiding on the ponies, and are threatening a war of extermination on the Potawatomies. And this rumor has so frightened our Indians, who had camped in remote parts of the reserve near the Pawnees, that in one day they all pulled their tents and fled panic-stricken. In consequence we are placed in the front exposed to the fury of the Pawnees. And there is not an Indian who is willing or who dares to share our danger.” (p. 507) See St. Mary mission in image.

Kickapoo-Pottawatomie Grand Indian Jubilee

The Life of Wah-bahn-se: The Warrior Chief of the Pottawatamies

SAC and Fox

Green, Charles. (1913). Early days in Kansas in Keokuck’s time on the Kansas Reservation. Topeka, KS: Kansas State Historical Society. The latter part of the book title—Being Various Incidents Pertaining to the Keokucks, the Sac and Fox Indians (Mississippi Band), and Tales of Early Settlers, Life on the Kansas Reservation, Located on the Head Waters of the Osage river, 1846-1870—gives a better idea of the nature of this publication. Green supplies short biographies, financial accounts, portraits, and numerous lists such as a listing of Sac and Fox agents or lists of traders with the Sac and Fox. Interspersed are notes, i.e., “In these years of the Civil War and after, because for a year or two some 4,000 refugee Cherokees and other Indians from the Indian Ty. had temporary home at Quenemo, several stores started up that divided up the profits until some firms broke up, as there were no white settlers on the Reservation.”

Wichita

Dorsey, G. A. (1904). The mythology of the Wichita. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. With the help of a Wichita interpreter, Dorsey gathered tales and variants from the Wichita living in Oklahoma. Stories include The Coyote and His Magic Shield and Arrows, The Story of Not-Know-Who-You-Are, The Woman Who Married a Star, The Old-Age-Dog Who Rescued the Chief's Son, and other stories used for the instruction of the young. Dorsey states the Wichita are a southern branch of the Pawnee and the Wichita he interviewed are remnants of three distinct tribes--Wichita, Waco, and Tawaconi--that all speak the same language.

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/501

Wedel, Waldo. (1959). An introduction to Kansas archeology. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Before describing key archeological sites in Kansas, Wedel discusses Kansas landscapes and tribes in this 723-page book.

John, Elizabeth A. H. (Autumn, 1983). A Wichita migration tale. American Indian Quarterly, 7(4), pp. 57-63. Considers various migration theories and stories. “A leading hypothesis is that the Arikaras, Pawnees, Wichitas, and Kichais derived from the ancient Caddo culture hearth centered about the great bend of the Red River; that a long process of northerly and westerly migration dotted their hamlets along the middle reaches of river valleys from Texas to the Dakotas. A contrary pattern, of southward movement, appears in the historic record and in legend. Perhaps the rigors of northern climate turned some back toward the milder valleys to the south. Surely another factor was hostile incursion by rivals for the resources of the Plains, an on-going process in historic times, when both Siouan-speaking and Anglo-American aggressors threatened the very existence of the old Caddoan village dwellers. (p. 61)

John, Elizabeth A. H. (1975). Storms brewed in other men’s worlds: The confrontation of Indians, Spanish and French in the Southwest, 1540-1795. College Station, TX: A and M University Press. John documents Caddoan movements southward. She cites Spanish and French sources that maintain that the Wichita occupied the Arkansas Valley from 1541 until the mid-1700s until Osage attacks forced them south to the Red and Brazos rivers.

Site References

Sources referenced on this website

Barr, Elizabeth. (1908). A souvenir history of Lincoln County, Kansas. Topeka, KS: Farmer Job Office.

Barry, Louise. (1963, Spring). Kansas before 1854. A revised annals, part nine 1836-1837,29(1).

Bernhardt, C. (1910). Indian raids in Lincoln County, Kansas, 1864 and 1869. Lincoln, KS: Author.

Berryman. Rev. Jerome C. (1923). A circuit rider's frontier experiences. Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, XVI, 211-219.

Blackmar, Frank W. (1912). Kansas: A cyclopedia of state history. Chicago, IL: Standard Publishing Company.

Blair, Ed. (1915). The history of Johnson County. Lawrence, KS: Standard Publishing.

Bragg, Caelin. (2023, March 30). Wichita State professor uncovers forgotten native nation that could ‘revolutionize’ history of the Great Plains. WSU News.

Carlisle, J. D. (1976). The history and culture of the Pawnee Indians.

Case, Nelson. (1893). History of Labette County, Kansas from the first settlement to the close of 1892. Topeka, KS: Crane & Company.

Catlin, George. (1841). Letters and notes on the manners, customs, and condition of the North American Indians, 2. New York City, NY: Wiley & Putnam.

Chalfant, William. (1990). Cheyennes and horse soldiers: The 1857 Expedition and the Battle of Solomon's Fork. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Chalfant, William. (1991). Without quarter: The Wichita Expedition and the Fight on Crooked Creek. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Chalfant, William. (1997). Cheyennes at Dark Water Creek: The last fight of the Red River War. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Chick, W. W. (1880, December 5). W. S. Chick letter to W. W. Conehouse, Kansas State Historical Society.

Choitz, John F. (1941). Ellsworth, Kansas: The history of a frontier town 1854-1885. Fort Hays, KS: Fort Hays Kansas State College.

Chouteau, F. (1918). Statement made by Frederick Chouteau, at Westport, Mo., May 21, 1880. In W. E. Connelley, Notes on the early Indian occupancy of the Great Plains. Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 14, 438–470.

Connelley, W. E. (1918). Notes on the early Indian occupancy of the Great Plains. Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, 14, 438–470.

Crawford, Samuel/War Governor of Kansas. (1911). Kansas in the Sixties. Chicago, IL: A. C. McClurg.

Custer, Milo. (1918, April). Kannekuk or Keeanakuk: The Kickapoo prophet. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984), 11(1), 48-56.

Cutler, William G. (1883). History of the state of Kansas. Chicago, IL: A. T. Andreas.

Dary, David. (1987). More true tales of old-time Kansas. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

de Mun, Jules Louis René, (1928). Journals of Jules de Mun. Missouri Historical Society Collections, 5(3).

Dixon, Benjamin. (2007). Furthering their own demise: How Kansa Indian death customs accelerated their depopulation. Ethnohistory, 54(3).

Dorsey, George A. (1904). The mythology of the Wichita. Washington, DC: The Carnegie Institution.

Dorsey, James Owen. (1916, January). Archaeological Bulletin,7(1)

Dorsey, James. (1894). A study of Siouan cults. In Eleventh Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Echo-Hawk, Roger C. (1992). Pawnee mortuary traditions. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 16(2), 77-99.

Ellsworth, D. A. (n.d.). History of Chase County, Kansas extracted from local newspapers.

Fitzgerald, D. (1988). Ghost towns of Kansas: A traveler's guide. University Press of Kansas.

Gershon, Livia. (2021, 13 January). Who was Charles Curtis, the first Vice President of color? Smithsonian.

Gray, Patrick Leopoldo. (1905). Gray's Doniphan County history: A record of the happenings of

half a hundred years. Bendena, KS: The Roycroft Press.

Green, Charles. (1913). Early days in Kansas in Keokuck’s time on the Kansas Reservation. Topeka, KS: Kansas State Historical Society.

Green, Charles. (1914). Sac and Fox Indians in Kansas: Mokohoko's stubbornness. Some history of the band of Indians who staid behind their tribe 16 yrs. as given by pioneers. Olathe, KS: n.p.

Hamilton, J. Taylor. (1901). A history of the missions of the Moravian Church. Bethlehem, PA: Times Publishing Company.

Hanschu, Jakob. (2018). Quantifying the qualitative: Locating burial mounds in north-central Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science (1903-), 121 (3/4), 261-278. Herring, Joseph. (Winter 2006-2007). Kansas History, 29, 226-224.

Harvey, Alexander Miller. (1917). Tales and trails of Wakarusa. Topeka, KS: Crane and Company.

Haskell Institute. (1914). Indian legends. Lawrence, KS: Haskell Printing.

Hawley, Marlin F. & Vehik, Susan C. (2012). Cultural and historical background. In Robert Hoard (ed.), Archeological investigations at Arkansas City, Kansas. Topeka, KS: Kansas Historical Society.

Hayward, Clarence E. (2010). The lost years: Miami Indians in Kansas. Kansas City, KS: Author.

Herring, Joseph. (1983/1984). The Chippewa and Munsee Indians: Acculturation and survival in Kansas, 1850s–1870. Kansas History 6, 212-220.

Herring, Joseph. (Winter 2006-2007). Kansas History, 29, 226-224.

Herring, Joseph. (1990). The enduring Indians of Kansas: A century and a half of acculturation. Lawrence, KS: University Press.

Hoard, R. J., Banks, W. E., Mandel, R. D., Finnegan, M., & Epperson, J. E. (2004). A Middle Archaic burial from East Central Kansas. American Antiquity, 69(4), 717-739.

Hollibaugh, E. F. (1903). Biographical history of Cloud County, Kansas. (N.P.): Humphrey & Company.

Hyde, George. (1951). Pawnee Indians. Denver, CO: University of Denver Press.

Irving, John T., Jr. (1835). Indian sketches taken during an expedition to the Pawnee and other tribes of the American Indians, Vol 1. London: John Murray.

Isely, Bliss. (1933). The grass wigwam at Wichita. Kansas Historical Quarterlies, 2(1), 66-71.

Johnston, Joseph E. (1857). Diary of Joseph E. Johnston while surveying the southern boundary of Kansas, with a glossary of Indian place names on the inside front cover. May 16 - October 29. [Special Collections Research Center, William and Mary].

Jones, Bruce. (1999). Archaeological overview and assessment for Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Chase County, Kansas. Midwest Archeological Center. Report No. 61.

Jones, Horace. (1928). The story of early Rice County. Lyons, KS: Lyons Publishing Company.

Jones, Lottie E. (1911). History of Vermilion County, Illinois: A tale of its evolution, settlement, and progress for nearly a century. Chicago, IL: Pioneer Publishing Company.

Jones, Paul. (1937). Coronado and Quivira. Lyons, KS: Lyons Publishing Company.

Kansas Academy of Science. (1906). Transactions of the annual meetings of the Kansas Academy of Science.

Kidder, Homer H. (1912). Biographical history of Barton County, Kansas. Great Bend, KS: Great Bend Tribune.

Lamb, Daniel. (1917). A history of the United States Army Medical Museum, 1862-1917. Washington Medical Annals, 15(1), 15-34.

Lockard, F. M. (1894). The history of the early settlement of Norton County, Kansas. Norton, KS: Champion.

Long, Eli. (1857). The Battle of Solomon Fork, 1857. https://www.hwy24.org/uploads/2/6/1/8/26189167/01_battle_of_solomon_fork.pdf

Lough, Jean. (1959, Spring). Gateways to the Promised Land: The role played by the Southern Kansas towns in the opening of the Cherokee Strip to settlement. Kansas Historical Quarterly, 25(1), 17-31.

Martin, Bill. (1916). In V. P. Mooney, ed., History of Butler County, Kansas. Lawrence, KS: Standard Publishing.

Martin, George, ed. (1906). Methodist missions among the Indians in Kansas. The Kansas Historical Collections, 9, 1905-1906.

Marshall, James O., & Witty, Thomas A. (1967). The Bogan Site, 14GE1: An historic Pawnee Village:

An appraisal of an archeological site in the Milford Reservoir, Geary County, Kansas. Topeka, KS:

Kansas State Historical Society.

Michno, Gregory, & Michno, Susan. (2007). A fate worse than death: Indian captivities in the West,1830-1885. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Press.

Mooney, Vol. (1916). The history of Butler County Kansas. Lawrence, KS: Standard Publishing Company.

Morgan, Perl. (1911) History of Wyandotte County Kansas and its people. Chicago, IL: Lewis Publishing Company.

Mosely, Charlton. (1992). Georgians on the Western Frontier: The Cheyenne Massacre and captivity of a Fannin County family. The Georgia Historical Quarterly, 76(1), 19-45.

National Park Service. (2020). Sarah Catherine White Brooks (civilian captive) 1850-1939.

National Park Service. (2020). Amanda “Anna” Belle Brewster Morgan (civilian captive) 1844-1902.

Nebraska Historical Society. (n.d.). Pawnee foods. https://history.nebraska.gov/publications_section/pawnee-foods/Nyquist, Edna. (1932). McPherson County, Kansas. McPherson, KS: Democrat-Opinion Press.

Riding In, James. (1992). Six Pawnee crania: The historical and contemporary significance of the massacre and decapitation of Pawnee Indians in 1869. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 16(2), 101-117.

Romig, Joseph. (1906). A brief sketch of Indian tribes in Franklin County, Kansas in 1862-1906. Kansas State Historical Society.

Root, Frank A. (1936, February). Kickapoo-Pottawatomie Grand Indian Jubilee. Kansas Historical Quarterlies, 5(1), 15-21.

Rydjord, John. (1968). Indian place-names. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Savage, Isaac. (1901). A history of Republic County, Kansas. Jones & Chubbic.

Schmitt, Karl. (1951). Wichita death customs. Chronicles of Oklahoma.

Schultz, F., & Spaulding, A.C. (1948). A Hopewellian burial site in the Lower Republican Valley, Kansas. American Antiquity, 13(4), 306-313.

Shults, J. W. (1911?) The legend of Geuda Springs. Wichita, KS: McCormick Armstrong Press.

Simons, John. (1971). A history of early day Barton County Kansas. Thesis. Emporia State University.

Spencer, Joab. (1909). Shawnee folk-lore. The Journal of American Folklore, 22(85), 322.

Stubbs, Michael. (2012). Fruitland: The Stanley Quaker Mission to the Kaw. Symphony in the Flint Hills Field Journal.

Switzer, Dale. (2023). Misremembered massacre. Lovewell History.

Tennal, Ralph. (1916). History of Nemaha County, Kansas. Lawrence, KS: Standard Publishing.

Throckmorton, George; Kingsbury, B. L.; Fry, H. A.; Hunt, Jane; et al. (1950). Historical Episodes of Early Coffey County.

Tomlinson, William. (1859). Kansas in eighteen fifty-eight. being chiefly a history of the recent troubles in the territory. Indianapolis, IN; Dayton & Asher.

Unrau, William E., & Miner, Craig. (1986). The Kansa Indians: A history of the wind people, 1673-1873. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Voigt, Barton. (1975). The death of Lyman S. Kidder. South Dakota History, 6(1).

Warde, Mary Jane. (2013). When the wolf came: The Civil War and the Indian Territory. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press.

Wedel, Waldo. (1959). An introduction to Kansas archeology. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Wedel, Waldo. (1946). The Kansa Indians. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science, 49(1), 1-35.

Wedel, Waldo. (1938, May). Kansas prehistory. Kansas Historical Quarterlies, 7(2), 114-132.

Werner, Morris W. (n.d.). Mosquito Creek settlement, Doniphan County, Kansas.

White, Leslie, ed. (1959). The Indian journals, 1859-62, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

(1891). Wild life on the Plains and horrors of Indian warfare. Saint Louis, MO: Royal Publishing Co.

Winsor, M. (1878). History of Jewel County, Kansas: With a full account of its early settlements and the Indian atrocities committed within its borders. Jewell City, KS: Diamond Printing Office.

Workers of the Writers' Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Kansas. (1939). The WPA guide to 1930s Kansas. Washington, DC: Works Progress Administration.

Wright, John. (1913). Dodge City, the cowboy capital and the Great Southwest. Wichita, KS: The Wichita Eagle Press.

Wichita Weekly Journal, April 16, 1890

For additional information, view the Kansas State Historical Society web page American Indians in Kansas.